What

is it that people find so powerful about Buddhism that they find the need to

appropriate it? Many people in America have taken aspects of Buddhism into

their own lives, even if they identify as another religion. Peacefulness and

mindfulness, the idea of leading a moral life, and the idea of developing

wisdom are all beliefs within Buddhism that many Westerners have begun to

believe. However, there are other beliefs that many people have yet to follow,

which is why people are appropriating and adjusting the religion to make it

their own.

At

first, I thought that people were secularizing the religion by taking certain

aspects of the religion and not others into their lives. Yes, there are some

ways in which Americans secularize the religion, such as by putting a monk on

an Apple ad. However, people are beginning to follow these beliefs because they

know that these aspects of Buddhism are teaching something about life. These

aspects of the religion are providing people with a means of guidance, which is

exactly what religion is for. Therefore, it is clear that Buddhism, even the

way that it is often used in pop culture is acting religiously. Also, often

times many celebrities are seen in pictures with the Dalai Lama, however the

Dalai Lama is as much of a celebrity himself. However, he isn’t respected like

that without reason; he is respected because he has something to teach. He can

help people, which is once again a way that he acts religiously.

The

fact that he is able to provide guidance, beliefs, and rituals for people, even

if people do not take in all of these beliefs, shows that he is acting in some

ways as a religion. Also, the reality is that people must appropriate different

aspects of life in order to make these aspects relevant now. There are areas of

all religions that have been appropriated because if everything was left the

same, then it would be so irrelevant and people would ultimately choose not to

follow any religions. People are so fascinated with Buddhism and its practices

because it is some form of “other,” but they are also enthralled with the way

that it can actually affect their lives today.

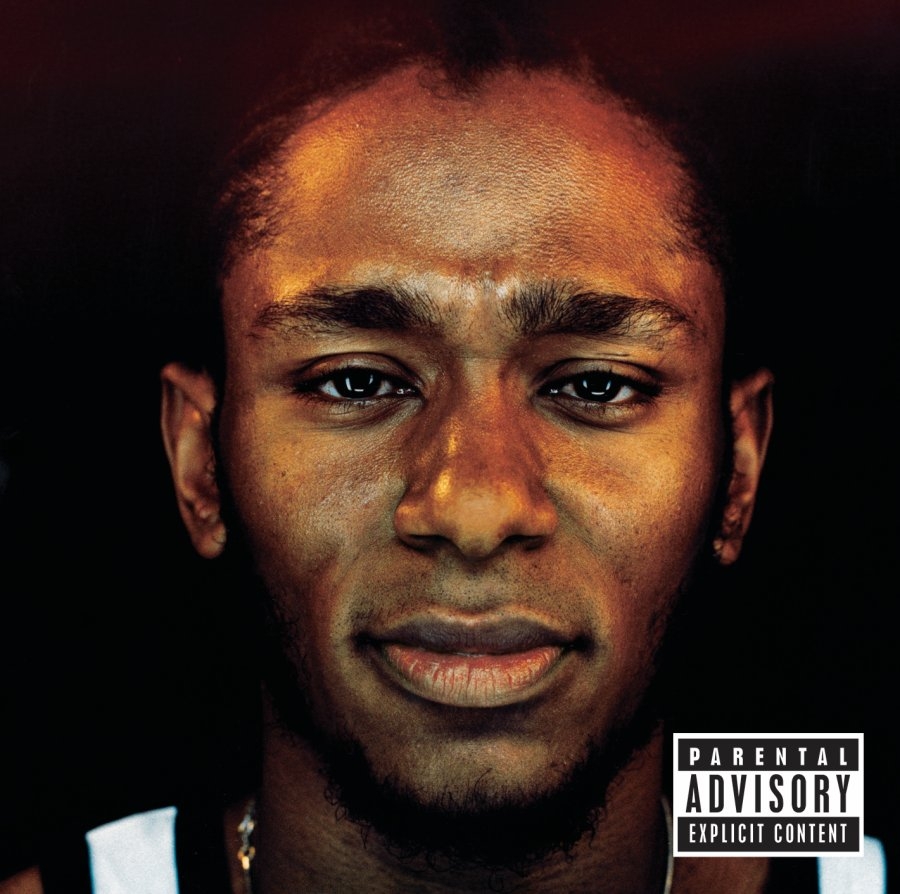

The

Dalai Lama shown on the cover of Vogue Magazine below is being in a form of

popular culture, but he is there because the editors of the magazine believed

that he had something meaningful to share with the readers. Jane Naomi Iwamura

characterizes the Oriental Monk as a “spiritual caregiver.” Although there are

negative connotations that come along with Orientalism in Western pop culture,

the idea of the monk as a caregiver seems to be a positive one because he is

able to provide something for those who choose to follow him.