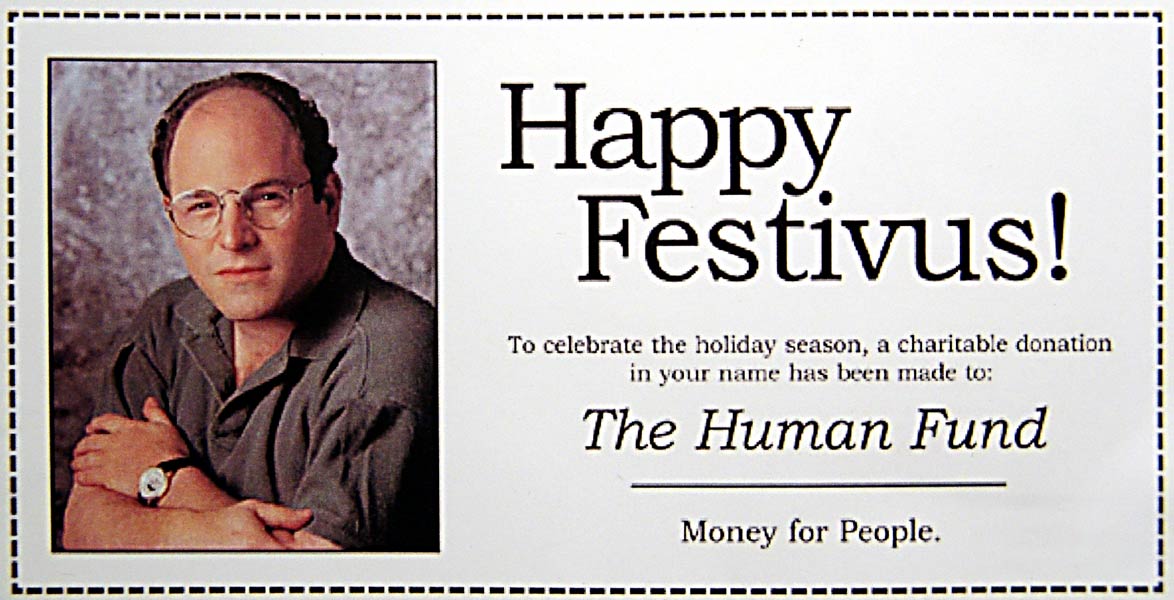

In Kumare and Seinfeld, we have seen the power of seemingly unauthentic religions. In Kumare, fourteen people followed the every teaching of a faux guru. His fabricated backstory and rituals provided legitimacy to his teachings. In many cases he was saying exactly what his followers had said to him but his authenticity brought their belief. In Seinfeld, George’s father creates the holiday of Festivus, equipped with a giant ceremonial pole and rituals like “The Airing of Grievances.” Both Kumare and Festivus have their own objects, teachings, events like many religions, however, we still would question considering these religious aspects as authentic.

As Chidester argues, “what counts as religion is the focus of the problem of authenticity” (9). Religion and American Pop Culture share many properties but that does not equate them. What is it that distinctly separates what is religious and what is not?